Contents

- ImageNet Pre-training & fine-tune paradigm

- Different modes of training

- Feature Representations and Random Initialization

- Related Work

- Normalization and Convergence Comparison

- Experimental Settings & Results

- Enhanced Baselines

- Experiments with less data

- Summary

Transfer Learning — the Pre-train & Fine-tune Paradigm

Deep learning has seen a lot of progress in recent years. It’s hard to think of an industry that doesn’t use deep learning. The availability of large amounts of data along with increased computation resources have fueled this progress. There have been many well known and novel methods responsible for the growth of deep learning.

One of those is transfer learning, which is the method of using the representations/information learned by one trained model for another model that needs to be trained on different data and for a similar/different task. Transfer learning uses pre-trained models (i.e. models already trained on some larger benchmark datasets like ImageNet).

Training a neural network can take anywhere from minutes to months, depending on the data and the target task. Until a few years ago, due to computational constraints, this was possible only for research institutes and tech organizations.

But with pre-trained models readily available (along with a few other factors), that scenario has changed. Using transfer learning, we can now build deep learning applications that solve vision-related tasks much quicker.

With recent developments in the past year, transfer learning is now possible for language-related tasks as well. All of this proves that Andrew Ng was right about what he said few years ago — that transfer learning will be the next driver of commercial ML success.

Different modes of training

In the blog Building powerful image classification models using very little data, Francois Chollet walks through the process of training a model with limited data. He starts with training a model from scratch for 50 epochs and gets an accuracy of 80% on dogs vs cats classification. Using the bottleneck features of a pre-trained model, the accuracy jumps to 90% using the same data. As a last step, on fine-tuning the top layers of the network, an accuracy of 94% is reported.

As is evident here, using transfer learning and pre-trained models can boost accuracy without taking much time to converge, as compared to a model trained from scratch. Does this mean the pre-train and fine-tune paradigm is a clear winner against training from scratch?

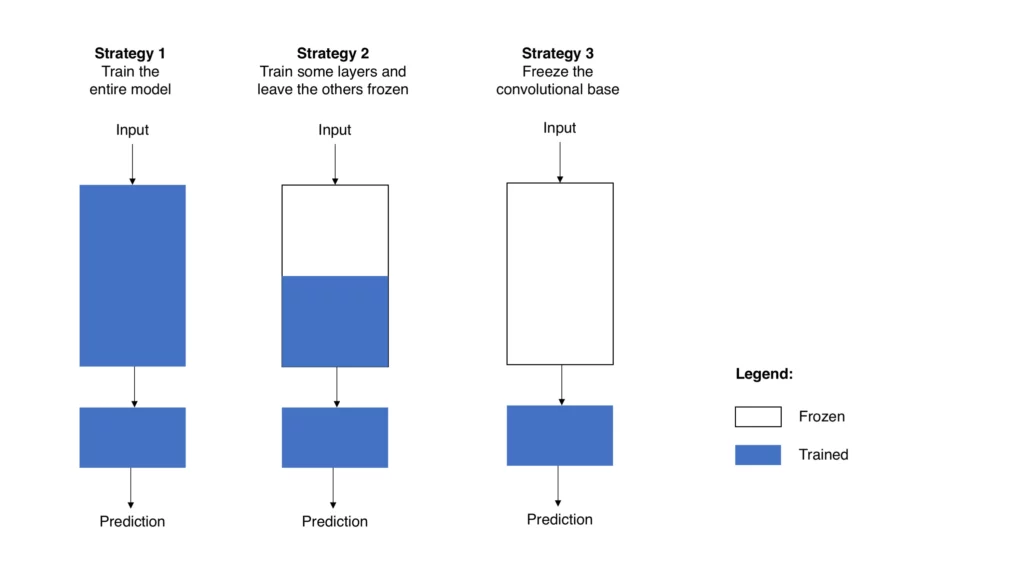

The above image helps visualize a few possibilities when training a model. The image on the right represents a model in which the convolution base of a trained model is frozen and the bottleneck features obtained from it are used to retrain the further layers. This is a typical scenario with pre-trained models. The image in the middle represents a model where, except for the few initial layers, the rest of the network is trained. And the final model on the left represents training a model from scratch—that’s the method we’ll be looking into in this blog.

In the pre-train and fine-tune paradigm, model training starts with some learned weights that come from a pre-trained model. This has become more standard, especially when it comes to vision-related tasks like object detection and image segmentation.

Models that are pre-trained on ImageNet are good at detecting high-level features like edges, patterns, etc. These models understand certain feature representations, which can be reused. This helps in quicker convergence and is used in state-of-the-art approaches to tasks like object detection, segmentation, and activity recognition. But how good are these representations?

Feature Representations and Random Initialization

Feature representations learned by pre-trained models are domain dependent. They learn from the benchmark dataset they’re trained on. Can we achieve universal feature representations by building much larger datasets? Some work is already done in this area, where datasets which are almost 3000 times the size of ImageNet are annotated.

However, the improvements on target tasks scale poorly with the size of the datasets used for pre-training. It shows that simply building much larger datasets doesn’t always lead to better results on the target tasks. The other alternative is to train a model from scratch with random weight initialization.

To train a model from scratch, all the parameters or weights in the network are randomly initialized. The experiments carried out in the paper Rethinking ImageNet Pre-training use Mask R-CNN as the baseline. This baseline model was trained on the COCO dataset both with and without pre-training, and the results were compared.

The results obtained prove that by training the model for a sufficient number of iterations and by using appropriate techniques, the model trained from scratch also gives comparative and close results to that of the fine-tuned model.

Related Work

If you’re used to working with pre-trained models, training from scratch might sound time- and resource-consuming. To interrogate this assumption, we can look at prior research done on training models from scratch instead of using pre-trained models.

DetNet and CornerNet use specialized model architectures to accommodate training models from scratch. But there was no evidence that these special architectures have given any comparative results to that of the pre-train & fine-tune paradigm.

In this work, the authors considered using existing baseline architectures with a couple of changes. One is to train the model for more iterations, and the other is to use batch normalization alternatives like group normalization and synchronized batch normalization. With this the authors were able to produce results that were close to that of the fine-tune approach.

Normalization and Convergence Comparison

If models are trained from scratch without proper normalization, it can produce misleading results, which might mean that training from scratch is not optimal at all.

For vision-related tasks, training data consists of images of high resolution. This means the batch size has to be adjusted accordingly to meet the memory constraints. Batch normalization works well with bigger batch sizes. The bigger the batch size, the better. But with high resolution images and memory constraints, model training has to limit its batch size to a smaller number. This leads to bad results with BN.

To avoid this, group normalization and synchronized batch normalization are used. Group normalization is independent of the batch size. Synchronized BN uses multiple devices. This increases the effective batch size and avoids small batches, which enables training models from scratch.

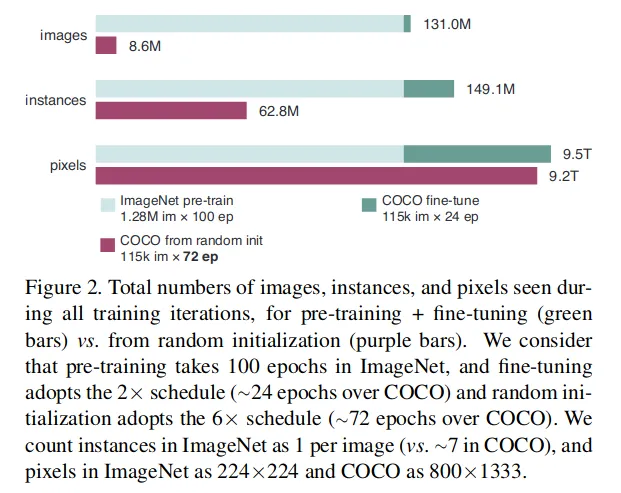

The fine-tuned models get kind of a head start, as the pre-trained model has already learned high-level features. That means the models trained from scratch cannot converge as fast as the fine-tuned models. Though this makes fine-tuned models better, one should also consider the time and resources it takes to pre-train a model on large benchmark datasets like ImageNet. Over a million images are trained for many iterations during ImageNet pre-training. So for the random initialized training to catch up, the model needs many training iterations.

The image here summarizes the number of training samples seen in both cases—with and without pre-training. Depending on the target task, the samples can be images, instances, or pixels. For a segmentation task, the model works at the pixel level. For object detection what matters is the instances of objects in each image. We see that except in segmentation (pixel-level task), training from scratch takes a substantially lower number of training images.

Experimental Settings and Results

Here are the experiment settings—the architecture and hyperparameters used. The experiments use Mask R-CNN with ResNet and ResNext architectures as the baseline. GN or SyncBN are used for normalization. The model is trained with an initial learning rate of 0.02, and it’s reduced by 10 times in the last 60k and 20k iterations respectively. The training data is flipped horizontally and there is no test time augmentation for the baseline model. A total of 8 GPUs were used for training.

By training a model with these settings on the COCO dataset with 118K training and 5k validation samples, the model trained from scratch was able to catch up in accuracy with that of a pre-trained model.

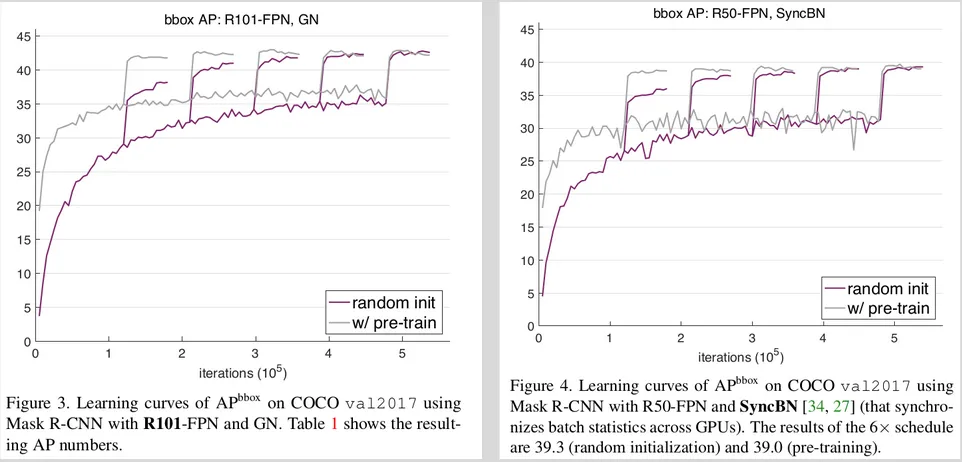

In this case, object detection and image segmentation are the two target tasks. Average precision for bounding boxes and masks are the metrics. As we can see in the plot above, the one on the left was trained with ResNet 101 and GN, whereas the one on right shows results for Mask RCNN with ResNet50 and SyncBN.

We see that when fine tuning, pre-training gives the model a head start, as we see the AP starts with a value close to 20. Whereas when training from scratch, the model starts with an AP value of close to 5. But the important thing to note is that, the model trained from scratch goes on to give close results. These spikes here indicate the results of applying different schedules and learning rates, all merged into the same plot.

Enhanced Baselines

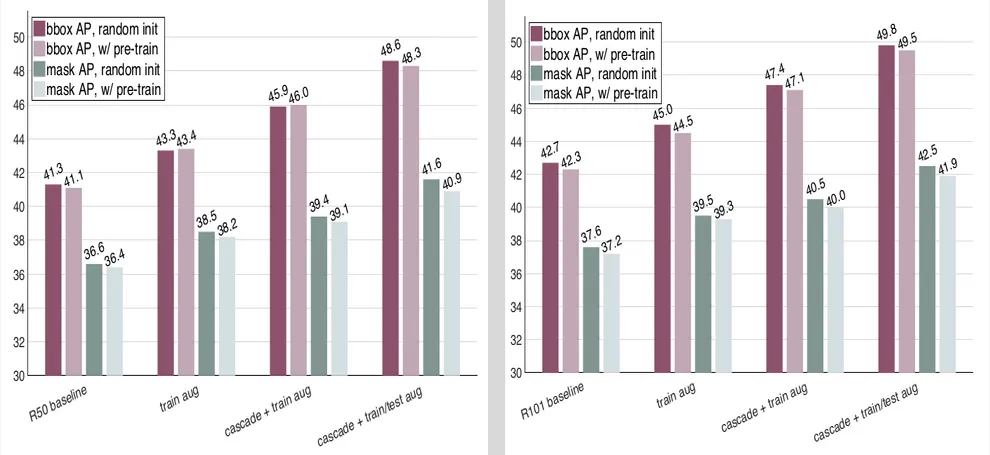

The authors also tried making enhancements to their baseline model. Better results were reported by adding scale augmentation during training. Similarly, using Cascade RCNN and test time augmentation also improved the results.

We see that with train and test time augmentation, models trained from scratch give better results than the pre-trained models. These plots show the results with enhanced baseline models.

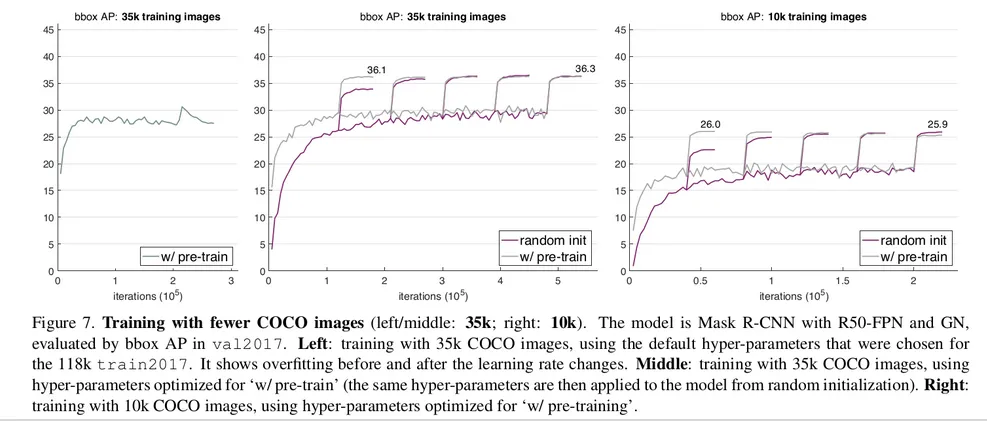

Experiments with Less Data

The final experiment was to try different amounts of training data. While the first interesting finding from this work is that we can get comparable results even with models trained from scratch, the other surprising discovery is that even when there’s less data, training from scratch can still yield close results to that of the fine tuned models.

When working with only 1/3rd of the whole COCO training data, i.e. close to 35K images, experiments show that the fine-tune approach starts overfitting after some iterations. That shows that ImageNet pre-training doesn’t automatically help reduce overfitting. But despite less data, training from scratch still catches up with fine-tuned results.

When only one-tenth of training data (close to 10k images) is used for training, a similar trend is noticed. We can see in the image on left—with the pre-train & fine-tune approach, the model starts to overfit after some iterations.

We see in the plots on the middle and right that training from scratch gives pretty close results to that of the fine-tuned models. What if we try with much less data? Like using one hundredth of the entire training data? When only 1k images are used, training from scratch still converges rather slowly. But it produces worse results. While the pre-trained models give AP of 9.9, the approach in consideration gives only 3.5. This is a sign that the model has overfitted due to a lack of data.

Summary:

- Training from scratch on target tasks is possible without architectural changes or specialized networks.

- Training from scratch requires more iterations to sufficiently converge.

- Training from scratch can be no worse than its ImageNet pre-training counterparts under many circumstances, down to as few as 10k COCO images.

- ImageNet pre-training speeds up convergence on the target task but does not necessarily help reduce overfitting unless we enter a very small data regime.

- ImageNet pre-training helps less if the target task is more sensitive to localization than classification.

- Pre-training can help with learning universal representations, but we should be careful when evaluating the pre-trained features.

Conclusion

The paper doesn’t claim that the pre-train and fine-tune approach is not recommended in anyway. But the experiments included have shown that for some scenarios, training a model from scratch gave slightly better results than the fine-tune/pre-train approach. What this means is that if computation is not a constraint, then for certain scenarios and configuration settings, the model trained from scratch gives better results than the fine-tuned ones.

This is an interesting study, especially because the pre-train and fine-tune paradigm is being used more as a standard procedure. And considering where deep learning is being applied—including use cases for automobiles, health, retail, etc., where even slight improvements in accuracy can make huge differences— it’s essential for research to not only aim for novel and innovative methods, but also to study existing methods in more detail. This could lead to better insights and new discoveries.

Comments 0 Responses