If you’ve ever done any MacOS or iOS development, you’ve also eventually had to deal with Xcode build settings.

So what are those and what do we know about them?

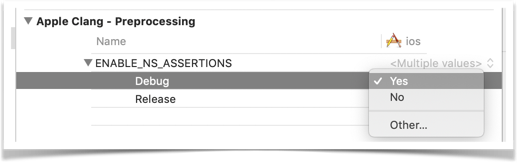

For a standard iOS project, there are roughly 500 build settings grouped into around 50 categories. These build settings control virtually every single aspect of how your app is built and packaged. At the very least, build settings are what make Debug build so different from Release build.

In this article, I’ll mostly focus on build settings that control the behavior of Apple Clang and Swift compilers and the linker.

🗄 Background Check

Build settings are not as simple as they may seem.

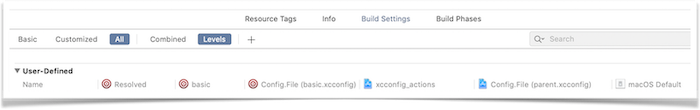

For starters, there are project- and target-level build settings as well as default OS settings.

The default OS build settings are inherited on a project level and project-level build settings are inherited on a target level.

Then there are .xcconfig files, which can be used to represent build settings in plain text format. The xcconfigs can be set on target and project level and add two more levels to inheritance flow.

To make things even more complicated, you can include other xcconfigs using C-like #include statements.

// MyApp.xcconfig

#include "Other.xcconfig"But there’s much more to build settings and xcconfigs.

To get familiar with all of the above, I’d highly recommend starting with The Unofficial Guide to xcconfig files. Check out the rest of this amazing blog for even more hands-on information about understanding and managing build settings.

⬇️ Level Down

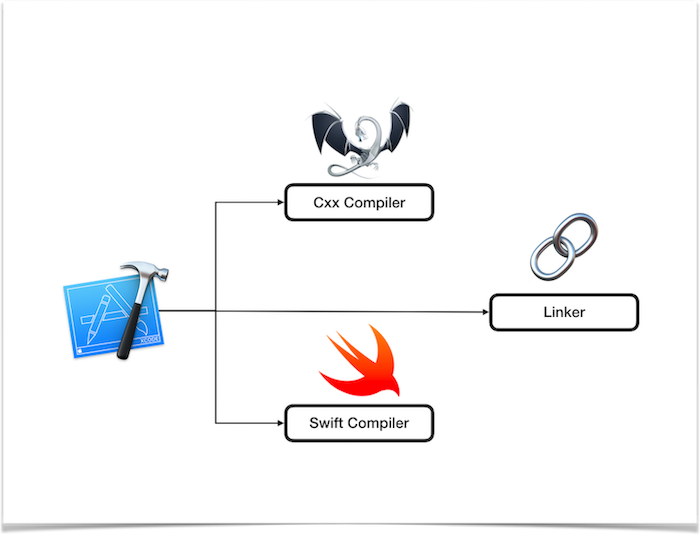

Now let’s go one more level down. When it comes to compiling and linking the source code, the Xcode build system manages 3 main tools under the hood:

- Clang Cxx compiler for compiling C/C++ and Objective-C/C++ code

- Swift compiler

- Linker to link all object files together

Each of those tools has its own set of command line flags.

Clang compiler and linker flags are documented here. The Swift compiler swift –help command provides a list of Swift command line flags. Surprisingly, I failed to find online documentation similar to Clang.

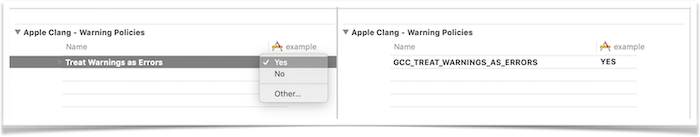

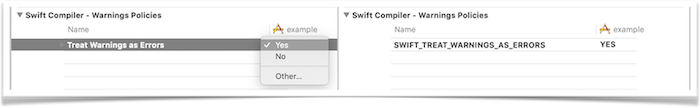

When a build setting is set in Xcode UI, Xcode then translates it to the appropriate flags for underlying tools.

For example, setting GCC_TREAT_WARNINGS_AS_ERRORS to YES will add a-Werror flag for the Clang Cxx compiler.

Similarly, setting SWIFT_TREAT_WARNINGS_AS_ERRORS to YES will

add a -warnings-as-errors flag to all invocations of the Swift compiler.

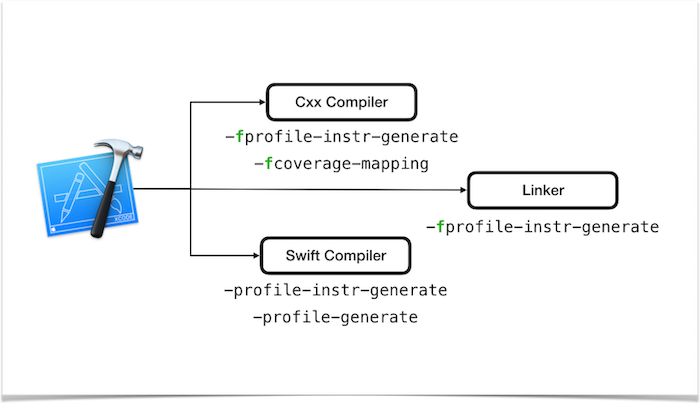

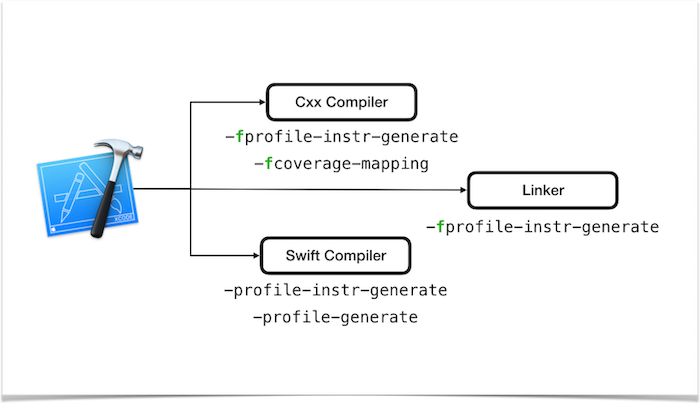

Finally, some build settings are translated into flags for all three tools; for example, enabling code coverage using the

CLANG_ENABLE_CODE_COVERAGE = YES build setting will translate into the following*:

- -profile-instr-generate and -fcoverage-mapping for the Clang compiler

- -profile-coverage-mapping and -profile-generate for the Swift compiler

- -fprofile-instr-generate for linker

— — —

— — —

So, how does Xcode know which flags to map build settings to? Where is this mapping information stored, and can it be extracted?

⚙️ Xcode Specs

The answer to the questions above is Xcode Specs or xcspecs.

Xcspecs are ASCII plist files with .xcspec file extensions stored deep inside the Xcode.app bundle.

Xcode uses these specs to render build settings UI and to translate build settings to command line flags.

There are xcspecs for the Clang compiler (Clang LLVM 1.0.xcspec), the Swift compiler (Swift.xcspec), and linker (Ld.xcspec), as well as a number of xcspecs for core build system and other tools.

These xcspecs reference each other and work together as a system. Each xcspec contains a specification for one or more tools. For example, Swift xcspec contains specification for the Swift compiler tool, while Clang LLVM xcspec contains specifications for the Clang compiler, analyzer, a couple of migrators, and an AST builder tool.

A tool specification includes such details as its name, description, identifier, executable path, supported file types, and more.

{

Identifier = "com.apple.xcode.tools.swift.compiler";

Type = Compiler;

Class = "XCCompilerSpecificationSwift";

Name = "Swift Compiler";

Description = "Compiles Swift source code into object files.";

Vendor = Apple;

Version = "4.0";

InputFileTypes = (

"sourcecode.swift",

);

ExecPath = "$(SWIFT_EXEC)";

// ...

};🔘 Options

In context of this article, we’re most interested in theOptions array entry of the tool’s specification, which is where information about build settings is stored.

For example, the value of SWIFT_EXEC is stored as an option and is used by Xcode to resolve the ExecPath = “$(SWIFT_EXEC)”; statement:

Options = (

{

Name = "SWIFT_EXEC";

Type = Path;

DefaultValue = swiftc;

},

// ...

)All build settings (options) have Name and Type properties.Name defines the build setting name, e.g. SWIFT_OPTIMIZATION_LEVEL.

Build settings may also have a Category, Description, and DisplayName properties. For example, the display name for SWIFT_OPTIMIZATION_LEVEL is Optimization Level.

A few build settings are hidden and never appear in Xcode UI. Some of them have a corresponding comment in the code like // Hidden, but not all.

Types

There are 6 different types of build settings:

- String

- StringList

- Path

- PathList

- Enumeration

- Boolean

ℹ️ String and Path

A build setting of String type has, well, a string value. Note that a string value doesn’t have to be quoted using double quotes.

As a matter of fact, some build settings that have integer values are represented using String type with the default value set to 0, but not to “0”.

Path type is almost identical to String when used in xcspecs. My guess is that Path type build settings are handled differently with regards to escaping whitespaces and other special characters. They also get special treatment when resolving wildcard characters like *.

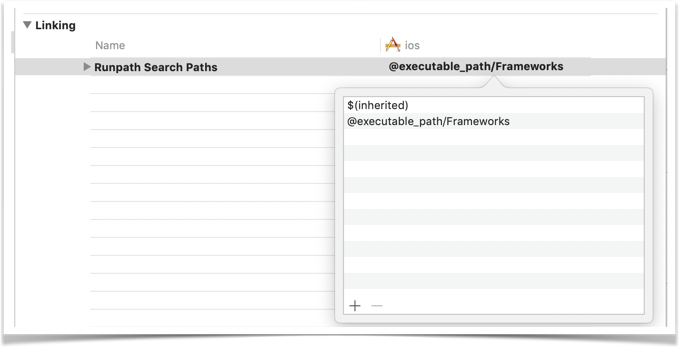

ℹ️ StringList and PathList

StringList and PathList are used to represent a list of string and path values, respectively.

If not provided, the default value is an empty list. You can define a list type in Xcode UI because it allows multiple values input:

ℹ️ Enumeration

Values of Enumeration type have a fixed list of values (cases), defined using a Values key, for example:

Name = "SWIFT_OPTIMIZATION_LEVEL";

Type = Enumeration;

Values = (

"-Onone",

"-O",

"-Osize",

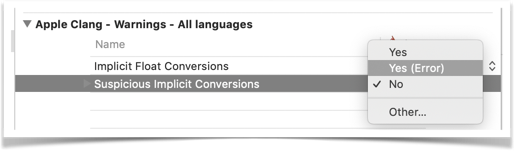

);Another good example is build settings that have a YES_AGGRESSIVE or YES_ERROR value on top of YES and NO. These build settings are declared as enumerations, too:

Name = "CLANG_WARN_SUSPICIOUS_IMPLICIT_CONVERSION";

Type = Enumeration;

DefaultValue = NO;

Values = ( YES, YES_ERROR, NO );

ℹ️ Boolean

Finally, values of Boolean type have either YES or NO values.

Note that only YES and NO are correct values for Boolean type, but not “YES” or “NO”.

🗺 Command Line Flags Mapping

As we already know, a lot of build setting values map to different command line flags.

The mapping information is defined in xcspecs using one of the following keys:

- CommandLineArgs

- CommandLineFlag

- CommandLinePrefixFlag

- AdditionalLinkerArgs

ℹ️ Command Line Arguments

CommandLineArgs key-value entry is used to map build setting value to a list of command line arguments.

Scalar Types

A good example is the SWIFT_MODULE_NAME build setting of String type:

{

Name = "SWIFT_MODULE_NAME";

Type = String;

DefaultValue = "$(PRODUCT_MODULE_NAME)";

CommandLineArgs = (

"-module-name",

"$(value)",

);

}The $(value) is resolved to the current build setting value, e.g. the MyModule value is mapped to the-module-name “MyModule” Swift compiler flag.

List Types

For list types, each build setting value in the list is mapped to one or more command line flags. For example:

{

Name = "CLANG_ANALYZER_OTHER_CHECKERS";

Type = StringList;

CommandLineArgs = (

"-Xclang", "-analyzer-checker", "-Xclang", "$(value)",

);

}If the value of CLANG_ANALYZER_OTHER_CHECKERS is “checker1” “checker2”, it will be mapped to the following:

-Xclang -analyzer-checker -Xclang checker1 -Xclang -analyzer-checker -Xclang checker2Enumeration Type

For enumeration types, mapping is defined for each enumeration case. For example:

{

Name = "GCC_C_LANGUAGE_STANDARD";

Type = Enumeration;

Values = (

ansi, c89, gnu89, c99, gnu99, c11, gnu11, "compiler-default",

);

DefaultValue = "compiler-default";

CommandLineArgs = {

ansi = (

"-ansi",

);

"compiler-default" = ();

"<<otherwise>>" = (

"-std=$(value)",

);

};

}- ansi value is mapped to the -ansi compiler flag

- compiler-default maps to no flags

- All other enumeration values map to the -std=$(value) compiler flag.

Note the use of “<<otherwise>>”—this is similar to default: enum switch in C-like languages.

Boolean Type

Boolean type is mapped just like enumerations with two YES and NO cases.

ℹ️ Command Line Flag

CommandLineFlag is used to prepend the command line flag to the value of the build setting.

For example, SDKROOT is defined like so:

{

Name = SDKROOT;

Type = Path;

CommandLineFlag = "-isysroot";

}So if the value of SDKROOT is iphoneos, the corresponding Clang compiler flag will be -isysroot iphoneos.

In a way, CommandLineFlag is shorthand for using CommandLineArgs. I.e. in the SDKROOT example, CommandLineFlag = “-isysroot”; could be replaced with CommandLineArgs = (“-isysroot”, “$(value)”); .

Handling of list, Enumeration, and Boolean types is similar to handling CommandLineArgs, too.

For example, given the definition:

{

Name = "SYSTEM_FRAMEWORK_SEARCH_PATHS";

Type = PathList;

FlattenRecursiveSearchPathsInValue = Yes;

CommandLineFlag = "-iframework";

}The value like SYSTEM_FRAMEWORK_SEARCH_PATHS = “A” “B” “C” will be mapped to:

-iframework "A" -iframework "B" -iframework "C"Enumerations deserve a special mention, because build flag mapping can be defined next to the value. A good example is MACH_O_TYPE:

{

Name = "MACH_O_TYPE";

Type = Enumeration;

Values = (

{

Value = "mh_execute";

CommandLineFlag = "";

},

{

Value = "mh_dylib";

CommandLineFlag = "-dynamiclib";

},

{

Value = "mh_bundle";

CommandLineFlag = "-bundle";

},

{

Value = "mh_object";

CommandLineFlag = "-r";

},

);

}ℹ️ Command Line Prefix Flag

CommandLinePrefixFlag maps build setting value to itself prefixed with a build flag.

It works just like CommandLineFlag. The only difference is that there’s no space between the build flag and the build settings value.

Good examples include LIBRARY_SEARCH_PATHS and FRAMEWORK_SEARCH_PATHS build settings of list type, where each list entry is mapped to -L”$(value)” or -F”$(value)”, respectively.

// LIBRARY_SEARCH_PATHS

"CommandLinePrefixFlag" = "-L"

// FRAMEWORK_SEARCH_PATHS

"CommandLinePrefixFlag" = "-F"Another similar build setting often used by developers is OTHER_LDFLAGS, aka Other Linker Flags.

Finally, whenever you see a flag like -fmessage-length=0 it’s most likely mapped using the prefix flag rule.

{

Name = "diagnostic_message_length";

Type = String;

DefaultValue = 0;

CommandLinePrefixFlag = "-fmessage-length=";

}ℹ️ Additional Linker Flags

Certain Swift or Clang compiler build settings map not only to compiler flags, but to linker flags as well.

Those build settings have an additional AdditionalLinkerArgs key-value pair. For example:

{

Name = "CLANG_ENABLE_OBJC_ARC";

CommandLineArgs = {

YES = (

"-fobjc-arc",

);

NO = ();

};

AdditionalLinkerArgs = {

YES = (

"-fobjc-arc",

);

NO = ();

};

}In this example, the -fobjc-arc flag will be added both to the Clang compiler and linker invocations.

The way mapping works for different build setting types is identical to the handling of CommandLineArgs.

References

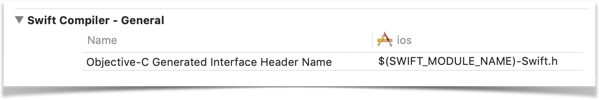

As I’ve mentioned earlier, build settings from different xcspecs can reference each other.

Some build settings have a DefaultValue property, which can reference other build settings, e.g. DefaultValue = “$(BITCODE_GENERATION_MODE)”;. The default value of some build settings is defined by referencing other build settings:

{

Name = "SWIFT_OBJC_INTERFACE_HEADER_NAME";

Type = String;

DefaultValue = "$(SWIFT_MODULE_NAME)-Swift.h";

}

The references can be nested as well. For example:

DefaultValue = "$($(DEPLOYMENT_TARGET_SETTING_NAME))";Here $(DEPLOYMENT_TARGET_SETTING_NAME) will be first resolved into a value like SOME_SETTING_NAME, and then $(SOME_SETTING_NAME) is resolved once again to a final value. This is similar to how build settings are resolved in xcconfigs.

Build settings reference can be used inside CommandLineArgs and all other mapping key-value entries.

Conditions

Conditions are defined using Condition key-value pair and are used to control whether or not a certain build setting is enabled.

For example, the SWIFT_BITCODE_GENERATION_MODE build setting only makes sense when ENABLE_BITCODE is set to YES:

{

Name = "SWIFT_BITCODE_GENERATION_MODE";

Type = Enumeration;

Condition = "$(ENABLE_BITCODE) == YES";

}Conditions have a C-like syntax, although string values don’t have to be quoted. Boolean operators such as !, &&, ||, ==, and != can be used:

Condition = "$(GCC_GENERATE_DEBUGGING_SYMBOLS) == YES && ( $(CLANG_ENABLE_MODULES) == YES || ( $(GCC_PREFIX_HEADER) != '' && $(GCC_PRECOMPILE_PREFIX_HEADER) == YES ) )";Other Properties

There are other properties, such as:

- Architectures — Defines which target architectures the build setting is applicable for.

- AppearsAfter — Controls the order in which 2 specific build settings appear in Xcode UI.

- FileTypes — List of applicable file types.

- ConditionFlavors — Must have something to do with the way conditions are checked.

- There are a few other flags I didn’t have time to fully investigate yet.

👩🏫 Example

Let’s have a look at one build setting example and see how we can apply all the knowledge from this article to figure out which flags it will map to.

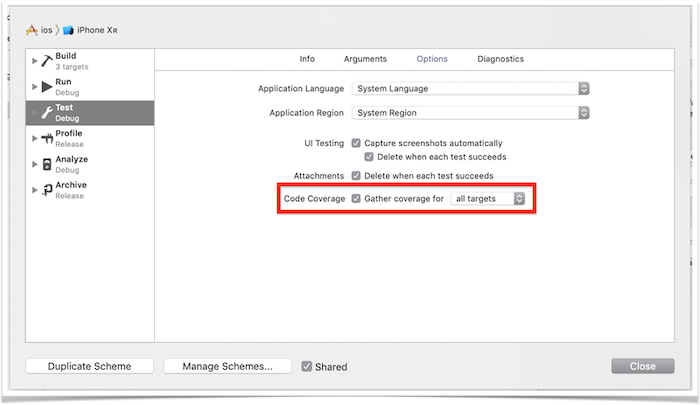

The build setting is CLANG_ENABLE_CODE_COVERAGE, and it enables one very important feature — code coverage.

CLANG_ENABLE_CODE_COVERAGE is defined in Clang LLVM 1.0.xcspec but strangely maps to no flags at all…

{

Name = "CLANG_ENABLE_CODE_COVERAGE";

Type = Boolean;

DefaultValue = YES;

Category = CodeGeneration;

DisplayName = "Enable Code Coverage Support";

Description = "Enables building with code coverage instrumentation. This is only used when the build has code coverage enabled, which is typically done via the Xcode scheme settings.";

}However, CLANG_ENABLE_CODE_COVERAGE is referenced by CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING.

{

Name = "CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING";

Type = Boolean;

DefaultValue = NO;

Condition = "$(CLANG_ENABLE_CODE_COVERAGE)";

CommandLineArgs = {

YES = (

"-fprofile-instr-generate",

"-fcoverage-mapping",

);

NO = ();

};

}So now we know the Clang compiler flags are added to the compiler invocation when code coverage is enabled.

Additionally, there’s another build setting that controls the linker flag:

// Extend the linker arguments when code coverage is enabled. We use a separate setting here to do this so that the extra linker flags will always be passed when code coverage is enabled, even if this specific target disables code coverage instrumentation via CLANG_ENABLE_COVERAGE_MAPPING.

{

Name = "CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING_LINKER_ARGS";

Type = Boolean;

DefaultValue = "$(CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING)";

AdditionalLinkerArgs = {

NO = ();

YES = (

"-fprofile-instr-generate",

);

};

}It also comes with a very detailed comment.

Finally, CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING is also defined in Swift.xcspec:

{

Name = "CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING";

Type = Boolean;

DefaultValue = NO;

AdditionalLinkerArgs = {

NO = ();

YES = (

"-fprofile-instr-generate",

);

};

CommandLineArgs = {

YES = (

"-profile-coverage-mapping",

"-profile-generate",

);

NO = ();

};

}Now all the pieces of the puzzle come together and it’s clear how Xcode does the mapping.

The only problem is that both CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING and CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING_LINKER_ARGS are hidden and don’t show up in Xcode UI. So how do those get set if they don’t reference CLANG_ENABLE_CODE_COVERAGE in their default value?

The code coverage can be enabled by editing the scheme in Xcode UI or by passing -enableCodeCoverage YES to xcodebuild invocation.

xcodebuild test -enableCodeCoverage YES # ...Xcode will then set both CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING and CLANG_COVERAGE_MAPPING_LINKER_ARGS to YES under the hood.

👷 Application

OK then, so it’s more or less clear how build settings are resolved, but what’s the practical application?

Well, there’s the purely academic application—you get to know how things work, which occasionally will come handy when you have a hard time figuring out various build settings messes.

While the official Xcode Build Settings reference page is a good resource to use, the extended Xcode Build Settings reference like this one includes information about compiler and linker flags, build settings cross-reference, and more.

But there are other ways to use this knowledge.

Let’s say you want to try out an alternative build system like Buck or Bazel. Those build systems are gaining popularity these days. Buck was created by Facebook while Bazel came from Google. Other companies such as Uber, AirBnB, and Dropbox use Buck; while Lyft is using Bazel to build their mobile apps.

Let’s further assume that over the years you’ve created and maintained a number of amazing xcconfig files. Those xcconfigs have all the compiler and linker build settings fine-tuned for your use. When moving to tools like Buck, you can’t just bring xcconfigs over. Instead you’d need to translate xcconfigs to compiler and linker flags and then use those with Buck.

Well, now you have all the knowledge to do so.

You’d need to start with reading and resolving xcconfigs and then map resolved build settings to build flags. It’s not a straightforward task and may take a while to implement. Luckily for you, there’s a Fastlane plugin that does just that.

Like many unofficial tools, this plugin is reverse engineering the ways Xcode works, so use it at your own risk.

Comments 0 Responses